Basics of Deep Learning¶

Introduction¶

Before we dive into some more advanced concepts in deep learning, let us recapitulate the fundamentals. Deep learning is a subset of machine learning, in which neural networks, which we will introduce shortly are trying to learn a mapping between samples from a dataset and their labels. In the 20th century researchers, inspired by how the human brain works, invented the Artificial Neural Network (ANN), whose architecture is depicted below. Frequently we also refer to this datastructure as a Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP).

Figure 1: Architecture of a Multi-Layer Perceptron¶

To create this particular network you need to execute this code:

>>> from nn import MLP

>>> from layers import Dense

>>> nn = MLP()

>>> nn.addLayer(Dense(inputDim = 3, outputDim = 4))

>>> nn.addLayer(Dense(inputDim = 4, outputDim = 2))

As you can see, you simply need to create a new MLP object and add the two dense layers by specifying the number of neurons in the input layer and the number of neurons in the output layer.

How can we compute the prediction of the neural network, given some sample from the dataset? In the following, we will answer this question for the case, in which subsequent layers of neurons are fully connected. These are the so called dense layers. For more sophisticated architectures and layer types, please go to the corresponding chapters.

In the simplest, case a Multi-Layer Perceptron only has weights and biases for each dense layer. Let us number these parameters from left to right, i.e. \(W^1\) (resp. \(b^1\)) denotes the weights (biases) between the red and the blue layer and \(W^2\) (resp. \(b^2\)) denotes the weights (biases) between the blue and the green layer. Then the prediction of the neural network is given by

for some input vector \(x\), since the i.th dense layer acts on an input vector \(x^i\) by

and we have \(x^1 := x\). The process of evaluating the prediction of a neural network, is called forward propagation, since an input vector is propagated through all subsequent layers of a neural network.

Activation functions¶

In general, the dense layers are not sufficient the way that they have been presented above, since they don’t contain any nonlinearities. Thus various activation functions σ have been introduced, which are applied to the output of a given dense layer, i.e. the i.th dense layer acts on an input vector \(x^i\) by

Which activation functions are there and which are suitable for my problem statement? There is a vast array of activation functions which have been developed by researchers, but we will only present you some of the most prominent examples, which have been also incorporated into our framework. The choice of activation function is somewhat of an art itself, but we would advise to try out the Sigmoid or ReLU function at first, since they have proven to be quite useful in practice.

In our framework we have implemented the functions:

Identity¶

The identity function \(f(x) = x\) is rarely used in practice, since it is linear.

>>> from activations import Identity

>>> f = Identity()

Sigmoid¶

The sigmoid function has been inspired by the neurons in our brain:

Neurons in the brain are either active, i.e. they fire, which is represented by a 1, or they are inactive, which is represented by a 0. Thus, the sigmoid function tries to emulate the function of a brain’s neuron, since for positive inputs the function’s value is close to 1 and for negative inputs it is close to 0.

Figure 2: Sigmoid function¶

Why don’t we use a step function, like the Heaviside function \(f\) with

Firstly, this function doesn’t have a derivative in the strong sense. Secondly, the variational derivative is 0 for \(\mathbb{R} \setminus \{ 0\}\), which would prevent the learning of parameters when applying backpropagation. Hence we use the sigmoid function instead.

>>> from activations import Sigmoid

>>> f = Sigmoid()

Tanh¶

Similar arguments to the ones presented above can be used to motivate the usage of the hyperbolic tangent

where \(\sinh(x) = \frac{e^x - e^{-x}}{2}\) is the hyperbolic sine and \(\cosh(x) = \frac{e^x + e^{-x}}{2}\) is the hyperbolic cosine.

Figure 3: Hyperbolic tangent¶

A major difference between the sigmoid and the tanh function is that for \(x \leq 0\) the activation function is now approximately -1. The hyperbolic tangent is used for example for LSTMs, which are a type of Recurrent Neural Network (RNN).

>>> from activations import Tanh

>>> f = Tanh()

ReLU¶

Although the previous functions were continously differentiable, they were costly to compute, since sigmoid and hyperbolic tangent require the evaluation of the exponential function. Thus data scientist choose to work with the Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU)

and its variations very often.

Figure 4: Rectified Linear Unit¶

Unfortunately the disadvantages of this simple activation function are that the function is not continously differentiable at 0 and that the slope of the function vanishes for \(x < 0\). These disadvantages can be eliminated by using the exponential linear unit (ELU) with

However, we haven’t implemented this function in our framework, since it also requires the evaluation of the exponential function. If we don’t want the gradient to vanish for negative inputs, we can alternatively use Leaky ReLU.

>>> from activations import ReLU

>>> f = ReLU()

Leaky ReLU¶

The Leaky Rectified Linear Unit (Leaky ReLU) differs from ReLU only by its function values for negative inputs.

Namely Leaky ReLU is weakly linear for \(x < 0\), instead of being 0 like ReLU.

Figure 5: Leaky Rectified Linear Unit¶

>>> from activations import LeakyReLU

>>> f = LeakyReLU(epsilon = 0.01)

Softmax¶

The Softmax function is used in the output layer of the network to yield a probability distribution over the different classes, e.g. when trying to classify whether there is a cat or dog in the picture we would like to know how certain the network is about its prediction. That is we would like some output like:

\(\mathbb{P}(\text{"dog"}) = 80 \%\)

\(\mathbb{P}(\text{"cat"}) = 20 \%\)

This type of prediction can be achieved with the formula

>>> from activations import Softmax

>>> f = Softmax()

Note

Activation functions can also be added to dense layers. If no activation function is specified, the layer uses the Sigmoid function. E.g. you can add ReLU to a dense layer via

>>> from layers import Dense

>>> from activations import ReLU

>>> denseLayer = Dense(inputDim = 3, outputDim = 4, activation = ReLU())

Loss functions¶

Now that we have established how the output of a neural network can be computed, we need to define a minimization problem, such that we can tweak the parameters of our neural network. For that purpose, we need the so called loss function which we are minimizing. The loss function is supposed to be an indicator for the quality of the neural network and depending on the function we choose, we get different results.

In our framework we have implemented the loss functions:

Mean Squared Error¶

The Mean Squared Error (MSE) describes the \(L^2\)-error between the predictions of the neural network and the expected outputs.

This kind of loss function can be used for regression tasks and we will for example use the Mean Squared Error when training denoising autoencoders.

>>> from loss import MSE

>>> loss = MSE()

Crossentropy¶

Given that the output of the neural network resembles a probability distribution, i.e. all output values are between 0 and 1, then we can use the Cross Entropy loss function. This is often being used for object classification tasks, since then a binary classifier is being trained for each object class. Hence all output values are between 0 and 1, where 0 means “doesn’t belong to the class” and 1 stands for “belongs to the class”. Thus we can use Crossentropy for our loss, since the output of the neural network is being forced to either be close to 0 or close to 1.

>>> from loss import CrossEntropy

>>> loss = CrossEntropy()

Note

A loss function needs to be specified when training the neural network.

Optimizers¶

Neural networks have a vast amount of parameters which can be tweaked such that a task, like for example object recognition, can be learned. How should we choose these parameters such that the neural networks excels at its task? An intuitive approach would be to brute force the optimal parameters or use an evolutionary algorithm. This is also being done in practice when working with tiny networks where only a few dozen parameters need to be tuned. For example, genetic algorithms like NEAT can be used to create programs that can play simple jump and run games like Super Mario. However, we are interested in tasks where we need neural networks with in the order of a million parameters. Thus, we instead use gradient based optimization methods like Stochastic Gradient Descent or Adam.

Let \(\theta\) denote the parameters of a neural network. In our case \(\theta\) consists of the weights and biases of the individual layers. Furthermore, let \(\eta\) be the learning rate which dictates how much the parameters can be changed.

Stochastic Gradient Descent¶

A key oservation is that differentiable increase the most in the direction of the gradient. Thus we would like to go in the opposite direction of the gradient, since there the function decreases the most. When scaling the gradient with the learning rate, we get the Gradient Descent algorithm

From the theoretical point of view, one should always compute the gradient of loss function evaluated on the entire training set. This is rarely advisable in practice, since it is computationally to expensive to evaluate the loss on the entire training set. Hence, the training set is being divided into smaller chunks called mini-batches and the parameters are being updated by only evaluating the gradient of the loss on a single mini-batch. This approach is being referred to as Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD).

>>> from optimizer import SGD

>>> optimizer = SGD(learningRate = 0.01, momentum = 0)

Adam¶

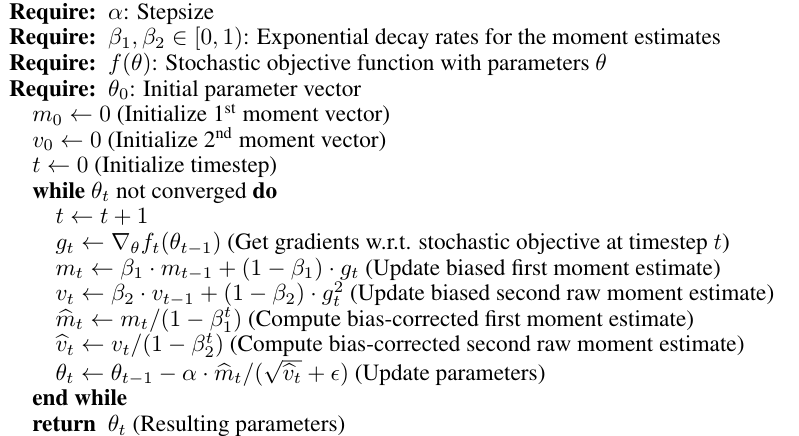

The Adam optimizer[3] tries to fix the shortcomings of gradient descent by introducing adaptive learning rates. Effectively this optimizer is a combination of AdaGrad and RMSProp.

Algorithm from the original Adam paper[3]¶

>>> from optimizer import Adam

>>> optimizer = Adam(learningRate = 0.001, beta_1 = 0.9, beta_2 = 0.999)

Note

Optimizers can also be added to dense layers. If no optimizer is specified, the layer uses Adam. E.g. you can use Stochastic Gradient Descent via

>>> from layers import Dense

>>> from optimizers import SGD

>>> denseLayer = Dense(inputDim = 3, outputDim = 4, optimizer = SGD(learningRate = 0.01))

Code: Training a Classifier¶

First we need to import all of our custom classes, which are needed to create a classifier.

>>> from nn import MLP

>>> from layers import Dense

>>> from activations import ReLU, Softmax

>>> from loss import CrossEntropy

>>> from dataset import Dataset

>>> from optimizer import Adam

Then we import the MNIST dataset which contains grayscale images of shape 28x28. It consists of 60,000 training samples and 10,000 test samples. We chose a batch size of 50.

>>> dataset = Dataset(name = "mnist", train_size = 60000, test_size = 10000, batch_size = 50)

Our classifier is a Multi-Layer Perceptron with 784 neurons in the input layer, 100 neurons and 50 neurons in the hidden layer, as well as 10 neurons in the output layer. We need 10 output neurons, since the classes of the digits have been one-hot encoded, i.e. \(\scriptsize 0\ \hat{=}\ \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \end{pmatrix}^T\), \(\scriptsize 1\ \hat{=}\ \begin{pmatrix} 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \end{pmatrix}^T\), etc. In most layers we use the ReLU activation function and in the output layer we use the Softmax function, since it outputs a probability distribution over the digits. All weights are being trained with the Adam optimizer, since it performed better than Stochastic Gradient Descent.

>>> classifier = MLP()

>>> optimizer = Adam(learningRate = 0.1)

>>> classifier.addLayer(Dense(inputDim = 28 * 28, outputDim = 100, activation = ReLU(), optimizer = optimizer))

>>> classifier.addLayer(Dense(inputDim = 100, outputDim = 50, activation = ReLU(), optimizer = optimizer))

>>> classifier.addLayer(Dense(inputDim = 50, outputDim = 10, activation = Softmax(), optimizer = optimizer))

Finally, we can start our training loop in which we are tring to minimize the Crossentropy loss. We are using 10 epochs, which means that the classifier is being trained on the entire training set 10 times. We also monitor these losses on the training and test set. Additionally, we log the predicition accuracy on the training and test set.

>>> classifier.train(dataset,loss = CrossEntropy(), epochs = 10, metrics = ["train_loss", "test_loss", "train_accuracy", "test_accuracy"], tensorboard = False, callbacks = {})

After training this classifier, which has been created with less than 15 lines of code, we can correctly predict handwritten digits in more than 97 % of the cases.

References¶

Aurélien Géron. Hands-On Machine Learning with Scikit-Learn and TensorFlow: Concepts, Tools, and Techniques to Build Intelligent Systems. 1st. O’Reilly Media, Inc., 2017. ISBN: 978-1-491-96229-9.

Michael A. Nielsen. Neural Networks and Deep Learning. Determination Press, 2015.

Diederik P. Kingma and Jimmy Ba. Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization. 2014. arXiv: 1412.6980 [cs.LG].